A-Cat: Differential Rudder System explained by Bailey White & Ravi Parent.

–

With the A Cat Worlds being held this week at Houston YC, it’s a good time to publish this Differential Rudder system description and functionality written and sent by Bailey White, in collaboration with Ravi Parent.

Renders not fully detailed, as not much time these days but drawings are worth to visualize what’s going on with rudder blades/winglets. Will continue refining and we’ll try to update these later on. Hulls are Scorpion scaled used as base start to illustrate Arno Terra’s Flying Carpet, before the D3 or F1 were launched.

First time we heard on differential was in Bermuda AC, on the bow down trim, we requested Martin Fischer to enlighten us.

Now this feature (without those AC50 restricting rules) can be found in the A-Class Foilers, and later taken to the Nacra 17 Olympic fleet.

Andrew Landenberger is the pioneer in modern A-Class to have implemented the first winglets which have evolve to current developments.

You can still foil down and upwind pretty good without differential system, but the added righting moment will get you to the next realm.

Text below by Bailey White & Ravi Parent. — Later updates / Results on the first tricky day at Houston 2022 A Cat Worlds that started today Sunday.

Differential Rudders in the A-Class Catamaran by Bailey White & Ravi Parent. –

One of the most interesting and quietly evolving developments over the last few years in the A-Class has been in the rudders.

It was not long ago that the idea of winglets on rudders was debated. A little more than a decade ago, I remember hearing the carbon fiber being ground off in the morning sun as what we would regard now as very small winglets were cut off in the Florida Keys due to concerns over too much drag in our racing in Islamorada.

Landy, Mischa and others continued the work in this area and Mischa became the first World Champion to run rudder winglets in 2012. His DNA C Board boat showed much improved downwind pitch control in the very windy Islamorada World Championship. Back then we were just looking to keep the bow out and sustained foiling seemed impossible.

Look at the still awesome Nikita light or Morelli and Melin A2 with short rudders designed to minimize drag upwind, especially on the windward side, and compare that that to a new boat to see the evolution. Much of this evolution has been incremental and stepping back shows:

- Canted to vertical rudder blades

- Roughly double in draft, even for new classic boats

- Much stiffer cross bars

- Increased use of cassettes

- Multiple dimensions of rudder adjustment beyond the classics of toe-in and rake

- Movement of rudder elevators farther down on the rudder

- Continually increasing size and design sophistication of rudder elevators

Look at foiling A-Class rudder from 2017 or beyond and you will be hard pressed to be sure if is from a SailGP fifty footer or an A-Class. Low drag, seagull-like designs minimize intersectional drag. Tips curl off to minimize vortices. Advanced airliner and drone wings have nothing on these.

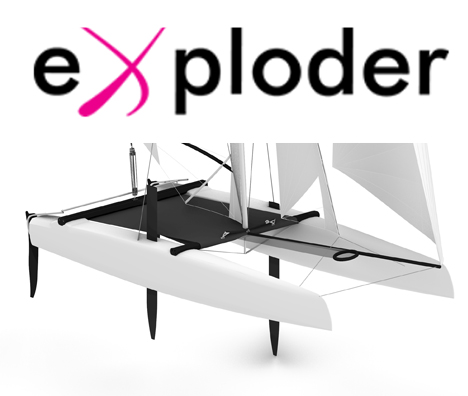

Along the route, fascinating innovations have occurred such as the Scheurer system to raise rudders from the wire to minimize drag upwind. Various approaches to elevator attachment, including a T system from eXploder that looked much like a 737 tail. L and T rudder shape design alternatives have converged to T.

How in the world are boats sailing with these in light air and still doing well when a decade ago we all were sure those tiny symmetrical fins added to small rudders were costing us the race? Credit the strengths of a development class and its sailors.

At the same time as the visible hardware changes manifested, a more internally-oriented adjustment system also evolved. A few years ago, every foiling sailor carried an Allen wrench or two to adjust his or her rudders on the water between races. Sometimes a 10mm wrench or even a screwdriver. Before that, I remember using pieces of popsicle sticks on my 2011 DNA C board boat to fine tune the rudder winglet angle. At one point in the foiling evolution, it wasn’t uncommon to see a sailor lying on his stomach in the back of the boat hanging over the transom adjusting rudders, sailing for a bit, and then adjusting more.

None of that happens anymore in the open class. Now sailors can adjust angle of attack of both rudders or even apply differential from the wire, opening up improved foiling and also the possibility of increased righting moment. The first, improving traditional downwind foiling through adjustment of both rudders when needed, was a straightforward evolution of the wrench work done previously at the back of the boat. It enables the sailor to quickly fine the foiling balance of the boat and take off in lighter air. Paul Larsen raced an early AD3 with a belt system he built between the rudders in the 2017 World Championship.

The next though, changing the rake of the rudders to increase righting moment, is a powerful addition in capability. The A-Class has always been a narrow and light boat and all of the sudden, the platform is increasing its sail carrying power. Other famous classes exploiting foil-driven righting moment are the IMOCAs, Sail GP F50s, and AC 75s. Not bad company! Like the F50s, the A-Class can now get righting moment from both rudders. The leeward rudder can now provide the lift that both rudders did previously through additional positive angle of attack. This lift counters the downward forces of the sail plan when heeled. The windward rudder can be raked forward at its head and aft at its base so that its elevator now has a negative angle of attack. Its windward hull lift can be removed and can even pull the stern of the windward hull down.

Numerous people experimented with systems to take advantage of this possibility but it took many years to develop the best approaches. C Class sailor and innovator David Sawicki was quick to recognize the potential of differential rudders, publishing a gear driven, tiller based differential system in a 2014 video that still has yet to be fully implemented on a race boat.

Regardless of the mechanical approach, differential rudder systems in the A-Class fall into two camps:

- Windward rudder lift reduction systems. These approaches allow the sailor to reduce the lift of the windward rudder and even pull on negative angle of attack in the windward rudder. The system is relative to the overall rake of both rudders.

- Proportional systems that shift the overall rudder rake between the two rudders. These systems can move, for example, zero degrees of overall rudder lift to be a negative rudder angle on the windward side and a positive rudder angle on the leeward side. The newest of these provide more linear response than older lever-based systems.

Sailing a boat with either system leads to unique experiences for most sailors. That immediate heeling from a gust as you sail upwind transitions to increased speed. Foiling downwind, the boat feels powerful and can go faster. Coming off the wire for a jibe, the boat can keep foiling as the rudder provides righting moment. Foiling upwind so much power can go into the boat that the mainsheet load increases to a level never experienced before. The capabilities of differential rudder systems are that substantial and can be proportional to speed.

How this will continue will be exciting to see. Much credit goes to the class builders and equipment suppliers who have enabled this course of development. A-Class catamarans have historically been known as fragile boats optimized for minimum weight as weight was drag. Platform racking was not desired but acceptable when the boat had straight boards and rudders. Now platforms are reacting new loads beyond traditional forces into the rig and sail. Sailmakers are adopting new design ideas with flatter sails, stronger materials, and sometimes going back to radial patterns. It is all working and gear failures are not common even though loads keep going up. The strength and robustness is impressive. Average speeds keep rising and, while so much is going on in the boats, the systems allow sailors to keep their heads out of the boat and focus on speed and racing.

Teo di Battista , 3° of Classic using Exploder Ad3 2016 version instead Scheurer .

I just heard that my great sailing friend and former CEO of Hobiecat Europe has passed. May The endless oceans…

...Report was sent by an F18 Sailor, if you want Hobies reported send your own, we'll publish as usual. Cheers.

Looks like in your report the Hobies are not really present. Suggest to rewrite the article.

Thanks for the great report Wik. Great battle.